Read my novel online – The Good, the Bad and the Beast – Part 1 Section 3

Ldong Tsomo, who came into this world in Yilhung, was only called Ma-gios in the village.

This name was given to him because of his strong character: he upheld his decisions as strongly as the roof of a palace is upheld by the columns stretching inside. He was resolute to a point bordering on obstinacy.

He grew up in a region where fields were covered with an emerald sheet of grass speckled with juniper shrub. The hills were dotted with haystacks and nomads smoking pipes, who herded cattle and sheep in quiet simplicity. A king was said to have lived in the area a long, long time ago. Gesar was his name, and his wife, whom he adored to infatuation, was called Singdzhang Dugmo. When the royal couple came riding to the area with their entourage, Singdzhang Dugmo fell so strongly for the area that her heart fell into it. That is how the enchanting place had come to be called Yilhung, that is, ‘fallen heart’.

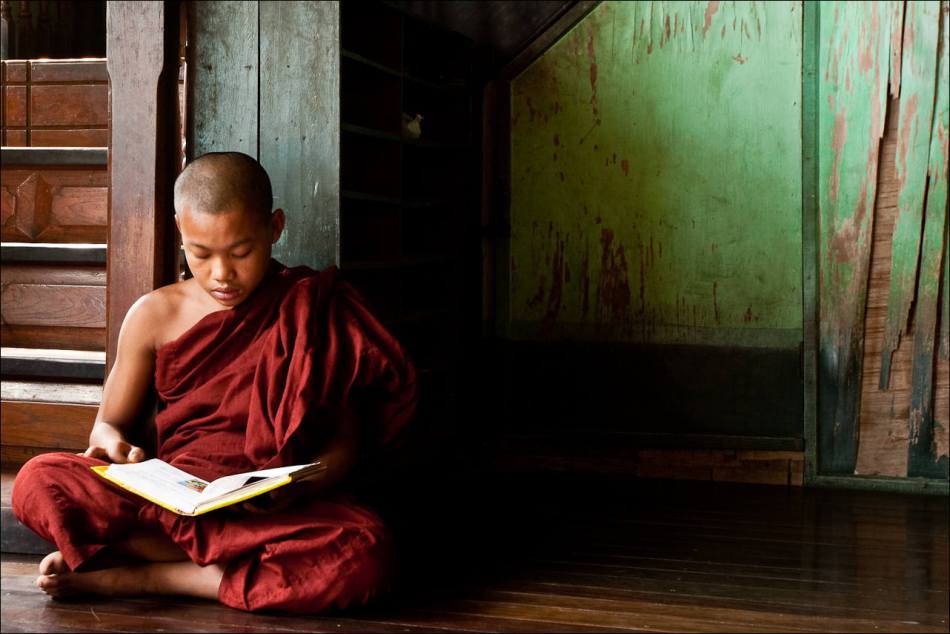

One day, menacing clouds gathered in the sky and Ma-gios’s mother died. Ma-gios was too little to understand why the neighbours leaning against the lattice fence were sobbing. Mum has closed her eyes and is having a little rest. She’s getting older. Why such a big fuss? But, out of sympathy, he sobbed along with the others. Towards the evening, the wailing ceased, and he was glad. All the lamenting really disturbed him, though he did find it a bit strange that Mum slept for so long. On the peaks of faraway mountains, murderously cold winds were forming fans of snow the size of football fields as if they wanted to unfurl flags at the highest peaks. Ma-gios began to fret because Mum did not want to wake up. He sat by her side the whole day, stroking the face that had already grown cold. A lama in a dark red robe came to their house on the third morning. Tactfully, his dad drew Ma-gios in his lap and they performed the necessary rites.

‘Does Mum ever wake up again?’ he asked his father, burying his little hands in his hand.

His dad shook his head in a strange way. In a harrowing way. As if he wanted to shake the whole day out of it and forget about what lay ahead. He was afraid of the future more than of loneliness. When neighbours, following Tibetan customs, carried away his wife’s dead body to a rocky place thirty miles away, Ma-gios’s father fell to his knees and sobbed.

‘Your Mum received a sky burial,’ he told his son. He cried for long after the neighbours and the lama had departed. Ma-gios later understood that his father was actually sorry for Mum’s body, which would be carried away by vultures and other wild animals. He had been cuddling that delicate body only a few days before.

Ma-gios only cried a week later. It was useless to hug him, he wept even more. He wept while stuffing grass into his favourite yak’s mouth, he wept while raking and he wept while playing with bugs on the walls of their house in the afternoon. He was so tired by the evening that he fell asleep sitting up.

‘He’s been purified,’ his grandma whispered, and dragged the blanket over his limp body. The movement woke him from his sleep, but he quickly closed his eyes lest they made him lie down. At night he had silly dreams: he had to fight a bear for a huge piece of cheese, which surprised him as he hated cheese wholeheartedly. His older relatives kept sucking at small broken cubes of petrified cheese. That was what must have made their teeth fall out, he supposed. He came to that conclusion by a simple deduction: if the mouth stinks of cheese all day, teeth probably fall out to flee the smell. He never ate cheese. If somebody smuggled it into his mouth surreptitiously, he spat it out instantly.

He stayed in bed until noon the following day but nobody disturbed him. Why doesn’t anybody come and take me to Mum? I’ve been sleeping long enough. Disappointed, he disentangled himself from the musty blanket that had protected generations from bitter Tibetan frost during its long life.

In the evenings he dreadfully missed Mum’s warmth, so he rolled up like a maggot to avoid being given a goodnight kiss by someone else. Grandma often sat on the edge of his bed, cuddled up to him, and put her shaking hand on his foot, which Ma-gios allowed. He didn’t move, but grandma’s touch gradually filled his broken heart.

‘Granny,’ he said one evening in the deep darkness, ‘why did Mum fall asleep?’

‘Well, I think she had to hurry.’

Uneasy movements began under the blanket.

‘Hurry? Why?’

‘You know, over there in the other world, there’s a monarch by the name of Dingtri who decides who needs to be reborn in what kind of other body. He has a palace with four gardens and there are seven stupas in each garden. If your mum meditates on Buddha for a year in front of each stupa, the monarch fulfils one of her wishes. So twenty-eight years are needed to fulfil one wish. That’s why she was in a hurry …’

‘And, Granny, do you know what she’s going to wish?’

‘Yes, I do.’

Ma-gios climbed from under the blanket. His eyes were almost burning the old woman’s skin.

‘She’s going to ask the monarch to let her be reborn as your child so that she can be with you for a long time to come.’

The little boy thought for a minute.

‘Would she really ask that, Granny?’

‘She would, really, so you shouldn’t weep any more,’ she whispered, touching his chin.

The sun came up like a burning pearl at dawn, squeezed itself between the sharp mountains and sprang into the sky. His father was calling the yaks to pasture with deep whoops, and they pushed out of the pen like black sacks straining against each other. Rabten, the neighbour’s teenage son, rubbed his eyes sleepily when Ma-gios’s father pushed a small bag of tsampa[1] into his hand for his shepherding journey. It was always his duty to take care of the animals while Father was away. Father’s scooter gave an ear-splitting noise when it started up, then he jumped on it and left along with the racket of the engine.

Ma-gios was left alone with his granny, who spent most of her days sitting, twisting yarn and spinning her prayer wheel. ‘Another identical day,’ he yawned. Without Mum, he felt even the brightest blue sky ashen. In the morning he read yet another new story from his book of legends with the foxed cover; in the afternoon he played with his sword at the sunny side of their house. His father was proud of him as he could read and write fluently at the age of five. He kept saying, ‘This boy’s going to become a monk.’

Now, however, chronicles of kings, ghosts and hidden treasures did not engage him. The sleeping sorrow woke up in his heart. He missed his Mum again so he put on his fur coat and, slipping by his slumbering grandmother, he made for the cliffs in the distance. He knew all too well that he was forbidden to go there, but they had been calling to him for a long time. I may catch sight of Mum. He had always thought the cliffs a frightening place. They were reputed to be fraught with ghosts and snakes, though he had never seen any when he had gone there with his father. More and more of his footsteps appeared on the sandy ground until only a long line could be seen with a black dot at the end of it. Perhaps I should’ve asked Rabten to look in on Granny, but it makes no difference now. He shrugged.

He valiantly climbed onto the first piece of rock, confidently dug his toes in the cracks cleft by ice and clambered towards the sky, pressing close to the ice-cold stone. Little pieces chipped off in his wake. He changed his grip swiftly just as he had learnt from his father. At last he got to the top of a rock the size of a house and triumphantly looked around the area, which looked as if a giant had cast huge rocks all around. There’s nothing frightening here.

He wanted to get to the foot of the mountain at least, so that he could revel in grandma’s expression of horror at hearing where he had been. He carefully climbed halfway down the rock, then jumped down at a suitable place. Unfortunately, he had miscalculated the distance, so, when he landed, he rolled over two or three times and scraped the skin off his elbow, making him wince. Further away, a golden eagle was flying close to the ground as if he had caught sight of something. The boy became excited. He may be watching a little animal, perhaps even a snake. Happiness intoxicated him, giving him strength to struggle over the next frigid rock. He didn’t take his eyes off the eagle; he followed the golden brown cross floating across the sky. In their youth, all creeping, crawling and burrowing animals learnt that death trailed in the shadow of that cross.

Something moved in the distance. At first it seemed to be a dry bush tossed by the wind. But no, the bush had paws and, instead of drab, dry leaves, it was the spots on the dirty white fur of a snow leopard that began to tremble. Hurling itself from rock to rock with long, springy leaps it was heading directly towards him. The distance between them was diminishing with benumbing certainty. The big cat jumped over the last rocks separating him from the boy in a leisurely fashion, apparently certain that he was going to have an easy breakfast. So the eagle was watching him. The thought flashed through Ma-gios’s mind, but the leopard was already on the neighbouring rock baring his teeth at him. I’m finished … he’ll kill me, he will!

He shrieked, ‘Daddy!’ as if hoping that his father could fly there and save him. On hearing the shriek, the leopard froze, but then started towards him at an easy pace. The hairs on Ma-gios’s arm stood on end. As he looked up into the sky, the shadow of the eagle slicing across the sun flitted over his face. His desperation changed into fury. But I don’t want to die! Deep inside his mind he felt a push, perhaps it was a needle pricking him, perhaps a blood vessel had snapped. His eyes flashed darkly, and a brash courage overcame him.

Preparing for the last, deadly jump, the leopard strained his muscles, but then stopped short. He watched, growling, as Ma-gios sprang from the rock, picked up a sizeable stone and threw it. It struck the leopard between his eyes with masterly accuracy. The boy’s his muscles hardened like steel and his arm seemed to work independently. He picked up more stones. The painful, bone-shattering throws showered on the perplexed predator were like hail. Confused, he flung himself from the cliff towards the boy, but another stone hit him on his head. He roared out in pain, unable to believe that the child of a man could defeat him, the king of the mountains. He hurled himself towards the little boy and, with mouth wide open, charged. The last sound that the king of the mountains ever heard was Ma-gios’s demonic laughter as the small hand clasping a fist-sized stone smote the leopard with superhuman force. With no time to avoid the strike, the animal tumbled like a sack and was lying in a pool of blood within a minute. Ma-gios was roaring the whole time, with a ghastly expression on his face. He tore off his outer clothes and knelt by the hairy creature soaked in blood. He grabbed the head of the leopard and bit into his neck. He tore off the velvety fur with pleasure and drove his teeth into the warm meat, then looked up to the sky again. The eagle was circling right above him now.

‘I’m the king!’ he shouted, raising his fist towards the sky, then, stretching out on the ground, passed out.

[1] A typical Tibetan staple foodstuff, a mixture of roasted barley flour and sometimes salty Tibetan butter tea.

Recent Comments