Just as life cannot rip through the swirling of death…

so the dawn sunrays could not break through the morning mist. Not yet. Death was lurking everywhere, watching for an opportunity to conquer all. Although only some murky image remained from her dream in her dawn oblivion, she opened her eyes with misgivings. She knew today would be different. Could Lhasa have changed overnight?

She grabbed the edge of her blanket and drew it up to her chin as if to defend herself. She did not feel like moving. It was dark, even though her digital clock indicated that the sun should have already come up. The shimmering light-green numbers of the display were staring her in the eye, and the vase standing beside it was dispersing the light like a prism. Beads of sweat gathered on her neck, although the hairs on her legs were bristling like broken reeds frozen on an icy lake. She turned her head to the side. Her habit was hanging from a peg, its pyramidal hood fallen forward. She strained to listen. Nothing moved. Silence filled the tiny room and only the barking of a faraway dog sawed into the lazily floating fog. She slipped her right foot from under the blanket first and set it down on the rough floor. The boards crawled lengthwise along the room. Under her sole, the bent head of a nail that had been clumsily hit into the boards pressed into her sole. A shiver ran up her spine. She sat up, wrapped the blanket tightly around herself and waited. She remembered forgetting her yak-fur slipper, leaving it on the doorstep the previous evening. Damn! Then something slammed at the windowpane with a terrifying crash. She lunged out of bed with the speed of a switchblade and sprang to the window. The muscles of her soles twitched on the freezing floorboards but that did not matter now. She gazed into the half-light, even opened one of the windowpanes, and held her breath. The yard, however, was empty.

Everywhere, fog was twirling. It sank into the water cask below the spout, which nurtured the mosquito larvae happily propelling themselves around in it like a brood-hen. It crept across the branches of the morello tree standing in the garden and stroked its leaves. Liang, her host, cultivated the morello tree, pruning it carefully each year out of respect for his younger brother, Kang, who had passed away tragically, becoming a hero in his brother’s eyes after he was shot dead by Chinese soldiers while protecting a Tibetan woman from their violence. Liang’s bereavement was deep and indelible.

The girl ran her fingertips along the window frame and drew a circle in the steamed-up glass. She looked up into the sky. The glitter of the evening star was melting away majestically in the drifting clouds. She shuddered, not with the cold but with the fear that was creeping into her heart. The darkness enveloped her naked beauty in awe. She drew another shape into the steam, turned, and hastily put on her clothes. Then she slipped out of the door but kicked a bucket over on the way, thus failing in her attempt to make a surreptitious exit. The bucket tumbled two or three times, jangling, then stopped. She waited a few seconds, pulled her red hood over her head and, cutting across the garden stretching behind the house, made for the gate. She slackened her pace when he reached the morello tree, where catnip was also copiously blossoming, took a leaf from Liang’s shrine and stuck it in her hair. She crushed a fresh shoot of catnip with her fingers. The tingling scent brought tears to her eyes, yet the usual peace did not come. She was gripped by dread. She hurried towards the Cuoqin palace, which, with its blood-coloured upstairs terrace and dhvajas[1] bent into the shape of brass top hats, cleft the early morning mist like a mythical steamboat. As soon as she reached the paved road, the mist began to thin, dispersing in the sunshine. With the light, strength returned her limbs. She did not notice when the leaf in her hair tumbled onto the ground. She had definitely come to the end of this path, her life in Tibet. At the edge of the asphalt snake, a truck with soldiers tarried, but she did not attach much importance to it. She felt protected in her monk’s robes.

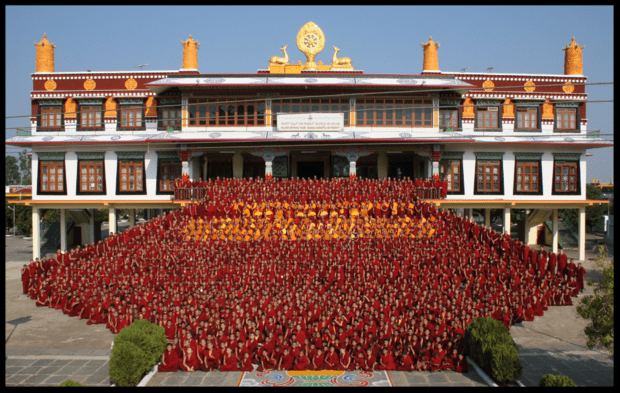

Her name was Angela Bergmann. She had fled to Tibet with her parents to hide from her pursuers. Her enemies were tirelessly trying to track her down, searching every nook and cranny for her because the treasure they were hunting so madly was hidden in her mind. Presently, however, she was not thinking of this treasure at all. She was caressed by sweet fancies. She looked into the sun and took a sniff of the air, which scratched into her lungs like diamond dust. She yawned and pressed her temples, knowing well that she had to hurry because the morning meditation in the palace would soon be over. She wanted desperately to talk to her friend, Ma-gios, before he plunged into his daily duties. Ma-gios lived in Drepung as a monk, had kept his sun-tanned head shaved close since childhood and followed the rules of sangha[2] – practically the rules of conduct of the monastery – to the full. He always turned his eyes towards the floor, or fidgeted with his crimson overcoat, while talking to her. At times he did not appear to be listening to her at all yet, later, he could recount the smallest details of their conversations. Angela was imperceptibly attached to this reclusive, slit-eyed, ball-headed, willowy monk who, politely but resolutely, refused her approaches. She was completely enchanted by him, although she would not admit this even to herself. She watched his movements and the more time she spent with him on the pretext of wanting to learn dharma[3], the more she admired him. She soaked up the saintliness of his words and together they listened to silence. Ma-gios was her guide in the night of her fears.

In the Cuoqin palace, which was a part of the Drepung monastery, the rinpoches[4] regularly admonished the indomitable, though charming, girl because she was constantly violating the rules. Yet, in their heart of hearts, they respected her studiousness and pursuit of knowledge. Though she was not allowed to take part in ceremonies, she could enter the palace when they had finished.

By the time she had skirted the wide-open space in front of the palace and reached the line of trees, she was out of breath. She hastened her pace but then, prompted by some inner instinct, turned back and glanced at the waiting truck. The dazzling sunlight reflected off the windscreen. Raising her eyebrows, she adjusted her hood and crossed between the trees. She suddenly caught sight of Ma-gios in the distance, bending at the foot of the red-painted columns as he swept the ground. Angela stopped. Her pulse was beating the time like a djembe[5] drummer. He’s there!

Ma-gios saw her and blinked, looking towards the trees, shading his eyes with his hands. Angela waved her hands, but the boy did not return her gesture. Why doesn’t he love me? But she knew this was a silly idea. Ma-gios loves everybody… She kicked a pebble and made for the stone steps that dominated the front of the palace, the truck and the soldiers forgotten. When she got to the bottom of the steps, Ma-gios waved to her. Still sweeping, he looked around furtively. The rising sun lit up a slight smile on his face. Angela mustered her courage. Without making a rustle, she climbed the steps and stopped a few paces from him. Ma-gios glanced at her. Rules bound the behaviour of bhikkhus[6] towards women, yet he eagerly obeyed every regulation as if he had pleasure in tormenting himself. Angela was also aware of these rigid principles, many of which she found outrageously stupid. She did not want Ma-gios to notice the revulsion she sometimes felt towards the rules of the monastery so she tried to smile, joined her palms and bowed.

‘Namaste!’

The boy propped his broom against a column.

‘Namaste,’ he answered and lowered his eyes.

‘Ma-gios, it’s such a pleasure to watch you … working,’ said the girl.

The boy looked up at her with his warm, brown eyes, which showed anxiety now.

‘You shouldn’t be here today, Angela. I’m worried about you.’

The wind whirled up an eddy of dust and flitted it along the steps.

‘Why?’ she asked with eyes wide open. She stepped closer to the boy.

‘You know well what the code says about contacting lay women.’

At that moment, an older monk, who had been lighting oil lamps nearby and was looking towards them with interest, stepped out of the palace. For the time being, he had no suspicions. Ma-gios felt Angela had a special effect on him. However much he was resolved in his mind to be beyond reproach, his resolution weakened when he was around her. He liked her, but dreaded her too.

‘You shouldn’t be here now.’ He took the broom in his hands again. From the corner of his eyes, he watched the other monk. ‘Cens whispered strange things about you in my ears tonight.’

Angela giggled and swept a ladybird off his robe. The other monk, still holding a burning oil lamp, turned towards them. He’s coming here. The thought kept throbbing in the young monk’s mind.

‘Well, who on earth are those cens? What makes them so clever?’ asked Angela, shaking her head.

Ma-gios sighed and said, ‘Please don’t touch my robe now…’

‘I’ve only saved you from a bug, I saw it attacking you!’

Ma-gios stared at her hard. ‘I don’t have to be saved! I can take care of myself.’

‘What’s the matter, Ma-gios? I’m listening. Who are those cens, anyway?’

Ma-gios cleared his throat and went on. ‘Well, cens are red spirits that inhabit the cliffs.’ He continued moving his broom across the pavement in careful circles. ‘They are the souls of monks of old times and have become the guardians of temples, altars and monasteries. They talked to me about you while I was in deep meditation. They’ve sent me a message: you should go home.’

‘Aha! Then what should I do now? Start running?

‘Perhaps that’s the best solution, but it may already be too late …’ He glanced towards the truck parked further away and lowered his voice to an ominous whisper, ‘You know, Angela, I’m worried for you. You’re a stranger without protection in this country.’

‘Well, you haven’t got a machine gun either, as a matter of fact.’

Ma-gios scanned the mountaintops in the distance. ‘My weapon is love.’

Angela was moved. Unexpectedly, she embraced the boy, but he became scared and ran away. She headed towards the palace. Dumbfounded, the monk on guard put his oil lamp on the ground as she glided by him to catch the boy.

‘Stare as much as you like,’ Angela whispered as she glided by him to catch her friend. ‘I know what you’re thinking. This prātimokṣa or whatchamacallit that you have to abide by may be good for the soul, but I’d reform a few of its rules.’

She entered the Cuoqin palace, but she could not see Ma-gios anywhere. He had vanished among the sea of columns. She passed her hand over the age-old wooden gate, its planks kept together by copper clamps, and stared at the columns; they enchanted her every time! Massive, fluted giants that had been wrestling with the weight of the roof for hundreds of years. They resembled the monks living here, except that the monks wrestled with their own desires and temptations. The air was more humid in the palace; she got a slight whiff of vanilla. Hundreds of flames flickered at the foot of Dawenshu’s statue, venerated by the monks. But the central place in the shrine on the third floor was, of course, taken by the statue of the Buddha. Eternal silence reigned there while, below, there were whispers in foreign languages and the flashes of tourists’ cameras. The enormous hall was supported by 180 columns (she had even counted them once), the walls were crowded by colourful thangkas – canvases painted with scenes illustrating Buddha’s divinity. Angela came to a stop at the foot of a column. She was still indignant about the prātimokṣa. Just as she had expected, Ma-gios soon returned, wavering for a moment before stopping beside her. Together they went to watch the flickering flames.

‘I didn’t want to be unfriendly to you, it’s only that …’

‘Yeah, I know, that wretched prātimokṣa!’

‘But, Angela!’

‘All right, I’m sorry! But what could happen to me in this ghost monastery? Haven’t your spirits told you?’

Ma-gios’s soul had become a keen biological radar over the years, capable of examining human souls, so he turned to Angela, ‘You Westerners know a lot, but knowledge unavoidably makes you self-important. I warn you that it’s one thing to know about something because you’ve learnt it and it’s another to know something because you’ve lived it. Don’t stay here, Angela!’

Before she could answer, he slipped away again. Alone once more, an inexplicable gloom descended on her heart. The peach-coloured lotus flowers painted on the ceiling seemed alarmingly far above her, making her feel the need to sit down.

In the front part of the hall, two monks lit a few more candles while others knelt beside them on their prayer cushions. The praying bhikkhus – from a distance tiny, blood-red pyramids – seemed to have found the connection between heaven and earth. Angela resignedly sank to her knees on the spot and began to pray. Words she had never used before rushed to her lips but she gave them free rein now.

‘God, You who live in holiness in the sky, please show me the way. I don’t know where my life is heading: my past has dispersed like fog, the present I don’t understand, the future disheartens me. I don’t understand why I’m here.’

With eyes bathed in tears, she bent down towards the floor and passed her fingertips over the worn flagstones and the centuries-old dirt stuck between them.

‘Please, answer me.’

The pressure inside her was growing. Something had to happen, something new and unfamiliar. What had so far been hidden must become evident.

‘Mysterious, invisible God, you’ve moulded me into what I am, you’ve followed me along the way. What future have you chosen for me? I’m begging you to show me now! Let me at least have the future, because I haven’t understood much of the past. It’s all jumbled and crazy like a bad dream. I must know the purpose of my life!’

As she pronounced the last word, she felt an overflowing happiness. Imagination took her into the unknown on its butterfly wings. She heard blue-feathered hummingbirds buzzing from branch to branch as their tiny bills slurped nectar from the flowers. Behind them, the sunrise glowing red on the horizon was swimming in clouds displaying the colours of rainbows. The morning dew was dripping in fat drops from the branches and the air was heavy with orchid-scented mist. Was this the answer?

She was about to pick a fabulous flower when someone settled beside her. Perhaps it’s a monk. But the person drew nearer and cautiously touched her hood. Angela woke with a start. A hard Chinese face looked back at her. Its owner held his index finger straight up in front of his pursed lips, clearly warning her to stay silent. His wrinkles were drawn into stiff half-moons around his eyes, steel-grey and glittering under his hood like those of a cat. He did not utter a single word. Instead of an explanation, he nodded in the direction of a blade, the size of a goose feather, in his hand.

[1] A sort of high column erected in front of temples in Hindu or vedic tradition

[2] Buddhist term for ’community’ (Sanskrit)

[3]A central concept of Indian philosophy and religion (more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dharma

[4] Precious one – honorific term of respect (Tibetan)

[5] Drum orinally from W-Africa (from Malinke)

[6] Buddhist monks

Recent Comments